From Cargo to the Court: Transport Paths Across Nunavut

By Katrin Schmid

There is a double basketball court across the street from Northmart grocery store in Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut Territory in Canada. During the summer of 2022, the court was missing a hoop and backboard, but the missing infrastructure is not what is of note here. From the outside these games look like any other round of pickup: kids shoot hoops, dribble and pass. The paths the materials took to enable a basketball court in Iqaluit, however, are particular to the territory.

When I asked people what is special about transport infrastructure in Nunavut, I was given similar answers in many different words: it is the “lack”, “limitations”, or “deficiencies”. And yet, Nunavummiut (residents of Nunavut) are highly mobile throughout the territory and along their connections to the rest of Canada. Nunavut is around 2 million km², the size of Mexico, and has a population of 36,000 – that is fewer than the Swiss canton of Obwalden, which is only 490 km². There are vast distances between Nunavut’s 25 municipalities and travelling throughout the territory takes time, planning, and a lot of money.

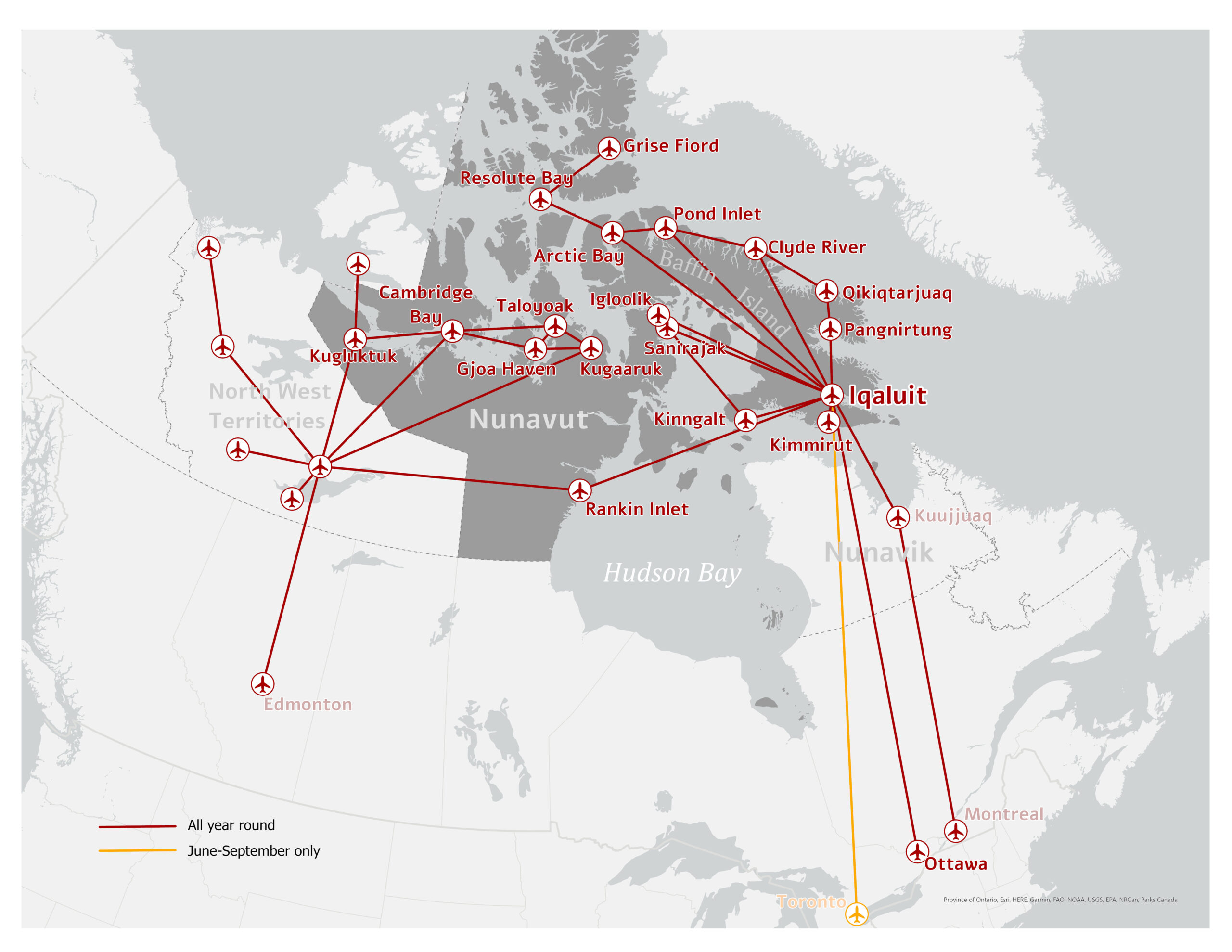

The most common mode of transportation between municipalities is air travel. Each municipality has an airport, but landing strips differ and this limits the type of aircraft that can reach individual communities. The capital’s airport is the largest in the territory. It was initially built as an air base for the United States military during World War II on land leased from the Canadian government. Now, Iqaluit is the hub of air transportation and the main gateway to and from the south. While airplanes make long-distance travel more efficient, it remains time consuming.

Today, Nunavut has two main passenger airlines servicing the territory’s communities, Calm Air and Canadian North. While Calm Air only operates in the Kivalliq region, Canadian North accesses the entire territory. However, the airline reroutes flights through Iqaluit in an effort to maximize passenger occupancy. As a result, if you want to fly from Pond Inlet to Cambridge Bay, you first have to fly to Iqaluit and then on to Cambridge Bay. Travels from Iqaluit to Gjoa Haven leap-frog you via Rankin Inlet, Yellowknife, Taloyoak and Kugaaruk before you reach your final destination.

Delays or cancellations are regular occurrences that need to be considered when planning a trip. With smaller aircraft accessing these northern municipalities, seats and cargo space are limited. In August of this year Canadian North announced a fuel shortage, causing flights to and from high Arctic communities to be cancelled or postponed until more fuel was obtained. Fewer seats were available and less cargo was transported because the airplanes had to carry more fuel than usual for their return trips. This is problematic because one of the main reasons Nunavummiut travel is for medical care in Iqaluit or one of the southern provinces. Cancelled or restricted flights simultaneously restrict access to medical services for northern residents.

Then why not hop into a car and scuttle down to the capital? Residents cannot drive from one hamlet to another because there are no roads connecting the communities (nor are there roads connecting Nunavut to the rest of Canada, for that matter). Snowmobile routes increase mobility throughout winter and spring but snowmobiles are expensive, as are their upkeep and fuel costs. The distances between communities mean travel takes several hours, or multiple days. Travelling requires time and an intimate knowledge of the land and potential risks.

Transportation across land or sea ice is heavily dependent on season. This seasonality also affects Nunavut’s principal way of transporting goods, including food, to hamlets: the annual sealift. The sealift is a series of cargo ships which transport containers full of ordered goods from the south to Nunavut communities. Iqaluit and other more southern hamlets are serviced by sealift up to three times a summer, but northern and western hamlets, such as Grise Fiord or Kugluktuk, only have one container ship arrive per year due to extensive sea ice coverage and long sailing times.

The high cost of air freight and the seasonality of cargo shipments means that large order items, ranging from snowmobiles and ATVs to water trucks and construction materials, are primarily transported to communities in summer. If a hamlet hopes to start a new construction project, they have to order every piece of material and equipment a year in advance or pay for it dearly via air freight. This does not leave much room for unexpected breakdowns and repairs. In communities where drinking water distribution is reliant on the operation of water trucks, bad roads or vehicle failure place residents in a potentially precarious situation.

Nunavut has the longest coastline of any Canadian territory or province yet there are few ports, none of which are public, even though all but one community are situated on the coast. In 2009, there were no small craft harbours in the territory. Since then, three communities on Baffin Island have received harbours. Two other communities were rewarded funding for small craft harbours last year. These planned infrastructures are an encouraging prospect to those involved in fishing and hunting, for example, because they could help lower the cost of harvesting as well as distribution of local foods.

Returning to the basketball court, those missing parts will be shipped up in next year’s sealift, or the City of Iqaluit may splurge and order them by air. Whereas other courts are reliant on dry weather to keep the dirt from turning to mud, the concrete court enables year-round games. In Iqaluit, kids play on a court that was made from materials and with vehicles that had been previously shipped up from the south, including the ball itself. Just as in most basketball games the ball is not moved from one end of the court to the other in one fluid motion; there are multiple legs to the journey. While the particularities of transport infrastructure in Nunavut may change the game, they do not stop it.

Please login to post a comment...