Indigenous Peoples and Infrastructure in the Arctic

By Timothy Heleniak

The Arctic countries have taken different approaches to categorizing people by race, ethnicity, nationality, or other identity characteristics, including a concept of indigeneity. Because of past migrations, the percent of Indigenous residents in Arctic regions differs considerably. These groups have been significantly impacted by non-indigenous populations, including through large-scale infrastructure projects. This blog post is based on Timothy Heleniak and Olivia Napper, chapter “The role of statistics in relation to Arctic Indigenous realities”, in Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic, 2020.

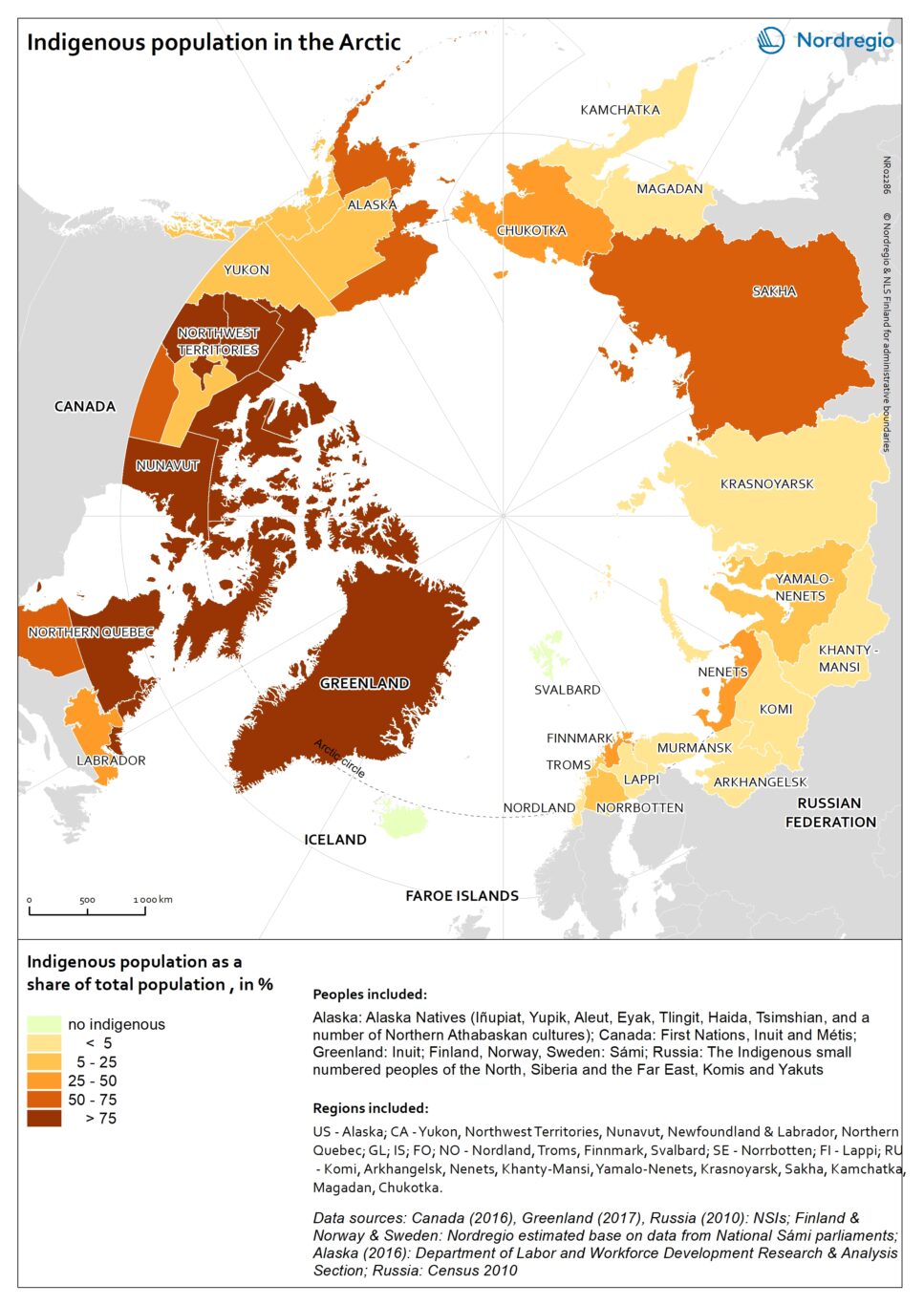

Percent indigenous peoples across the Arctic

There is no global or circumpolar definition of Indigenous, therefore the number of Indigenous people shown in the map is based on different national definitions. The Indigenous population is the highest in the Canadian Arctic and in Greenland, where they are more than 75 percent of the total population. In Sakha (Russian Federation) and the southwest region and northern region of Alaska, between 50 and 75 percent of the population is Indigenous. In Arctic regions where there has been considerable in-migration for resource development, the percent Indigenous is less than 25 percent. This includes much of northern Fennoscandia and western Russia. There are no Indigenous people in Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Svalbard. At lower geographic levels, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations are often quite segregated with Indigenous peoples residing in rural areas and outsider populations living in newly developed urban settlements built for resource extraction or transport.

History of categorizing peoples and defining Indigenous population groups in the Arctic

Concepts of identity, indigeneity, race, and ethnicity are social constructions and are thus fungible over time, space, and circumstance. The Arctic states have long sought to categorize the Arctic population peoples they encountered as they expanded state control northwards according to western/colonial norms. All Arctic states regarded the Indigenous peoples they encountered as being at lower levels of development. How statistical authorities producing censuses, surveys, and administrative statistics classify people is often at odds with how people view themselves. The Arctic states variously categorize peoples’ identity by race, ethnicity, place of birth, or have done away with these categories altogether as racist.

The United States classifies people based on race, a trait based mostly on phenotypes or observable characteristics. In the first U.S. census in 1790, there were three categories – white, black, and mulatto (mixed black and white). With immigration and the recognition of other minority groups the number of racial categories has increased. A category for American Indian was added in 1870 and Alaska Natives were included in this category. In 2000, the category was expanded to read “American Indian or Alaska Native”.

The first national censuses in Canada were the 1851/2 and 1861 enumerations. In these enumerations, the concept of “origin” was developed. Given that Canada was largely an immigrant country, people could not state that they were Canadian, except for the Aboriginal population, who were classified as “Indian”. Today, data on the ethnic origin of people in Canada are collected during censuses from the question “What were the ethnic or cultural origins of this person’s ancestors?”. There is a subsequent question which asks “Is this person an Aboriginal person, that is, North American Indian, Métis or Inuit (Eskimo)?” Canada’s classificatory scheme for Aboriginal ethnic origin has faced linguistic and logistical problems, but it has also had implications on Aboriginal land claims and status.

The conducting of censuses and collection of other data on the population and economy of Greenland was initially carried out as part of the statistical system of Denmark. Counts were made of the number of “half-breeds”, typically marriages between Greenlandic women and stationed Europeans. Starting in 1830, censuses became more regular, taken every 5 or 10 years. A distinction is made in those censuses between Natives and Europeans. Greenland currently categorizes people based on place of birth, the main distinction being in Greenland or outside Greenland. This distinction can be roughly thought to be native Greenlanders or non-Greenlanders, or Inuit or non-Inuit.

Norway, Sweden, and Finland are considered together because the Indigenous peoples in the northern regions are the same, the Sámi, and the treatment of them in censuses and statistical registers is similar. The Sámi people are spread across those three countries plus Russia in the Sámi homeland called Sápmi. Starting in the 1600s there were increasing numbers of researchers, administrators, and travelers visiting Lapland. Sweden established the world’s first statistical record of the entire population, the Tabellverket, in the 1600s. Responsibility for keeping records was shared between the clergy and the state. There were no explicit instructions regarding the Sámi population.

Likewise, Norway began to include a question on ethnicity in censuses in 1845 during a period when there was increased interest in defining the non-Norwegian population. Between the start of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, there was a policy of assimilation of minorities or forced “Norwegianization”. The last years of World War II had a devastating impact on the populations of Lapland, including the Sámi, which included border changes, transfer of territories, and forced migration. There seemed to be a declining interest in classifying people according to race as result of the Holocaust experience.

The Soviet Union was, and Russia remains, an ethnically and linguistically complex country. When the Bolsheviks came to power after the 1917 revolution, they needed to make sense of the multi-national empire they were presiding over. Through a complicated process, they settled on the concept of “natsionalnost” (better translated as ethnicity) as the term used to divide people into different groups and is still used in post-Soviet Russia. They used the results of the first all-union census in 1926 after creation of the Soviet Union to demarcate ethnic homelands including those of the Arctic and Siberian peoples.

Infrastructure development and Indigenous peoples in the Arctic

Infrastructure development in the Arctic has had a significant impact on Indigenous populations, both positive and negative. Positive impacts include increased and better access to markets, government services, and the outside world. Negative impacts include the building of roads or resource extraction in areas of traditional pastures for reindeer herding or damming of rivers which had been used for fishing. Decisions on infrastructure development in the Arctic are usually made by outsiders and have only recently begun to consider their impact on Arctic Indigenous populations in the form of environmental and social impact assessments. The InfraNorth project is neutral as to whether transport infrastructure projects are positive or negative and aims to include all residents of the Arctic and include their views on how transport infrastructure impacts their daily lives.