Remote Yet Hyperconnected: Svalbard Airport and Community Transitions in Longyearbyen

“If you arrived in autumn, you would stay up here until the spring or summer. We did not have any possibility to get down [to the mainland]. It was quite fantastic in many ways. It was a completely different society. It used to be calm here. You knew more or less everyone. You’d greet everyone. People were friendly, you would go to the store, and you’d talk to people. Unlike today, where people are rushing around. But of course, to be isolated up here was tough for many. If something happened to your family, you didn’t have the opportunity to travel down [to the mainland]. You just received a telegram that ‘grandma has died’ or ‘mother is sick’.”

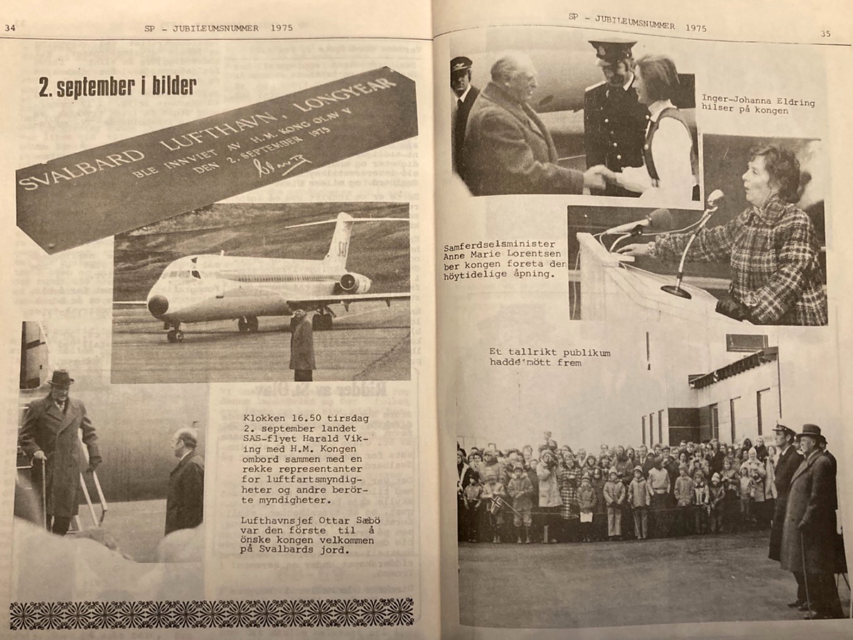

Over several cups of coffee one early afternoon in April, nestled in a quiet corner of the pub Kroa in Longyearbyen, Magnus reminisces about the pre-1975 era, when the construction of the Svalbard airport marked the end of winter isolation in the region. He is among the few who grew up in Longyearbyen and still live there. I invited him to share his memories and reflections about how the airport impacted life in this northernmost permanently inhabited Arctic settlement. Longyearbyen, located at 78 degrees North, is simultaneously extremely remote and hyperconnected to the rest of the world due to a modern airport connecting the archipelago to the Norwegian mainland. The airport, which opened in 1975, has been fundamental in bringing about the various societal transitions Longyearbyen has undergone. Established as a coal-mining camp, the former company town underwent phases of “normalization” and economic liberalization. Today, it is a tourist town and polar research hub, with an international and transient population of 2600 inhabitants. With coal mining currently being phased out, Longyearbyen is envisioned to become a showcase for green solutions in the Arctic, which also calls into question the hyper-mobility of its residents and the tourist industry.

The pre-airport society Magnus describes above was the “company town” of Longyearbyen, run by the coal mining enterprise Store Norske. It was inhabited predominantly by young Norwegian males working in the mines. The seasons dictated the rhythm and character of society. After the last boat left the archipelago right before the Barents Sea froze over and the dark season crept upon the Arctic, Longyearbyen was isolated from the rest of the world. The isolation ended when the first boat arrived in May or June. Coal boats, tourists, and researchers came and left, and workers, provisions, mail, and equipment arrived. Magnus recalls:

“The first boat was a big deal. People went down to the harbor to greet it. We got fresh food, fresh potatoes, fish for the people. And the miners and the grown-ups got beer!”

Throughout the 1960s, the state signaled that Longyearbyen was to be modernized and “normalized”: the company town should become more like other Norwegian towns on the mainland, with social infrastructure supporting a family society and a more permanent population. Store Norske was nationalized and state investments in infrastructure development increased. The opening of the airport was a central step in this process and is often described as a game changer. Magnus remembers that,

“People looked forward to the opening of the airport. If you got sick and needed to go down [to the mainland], now you could, it was like a safety net for the whole society. And we were no longer self-sufficient. You had the opportunity to get help and food. And not least to be able to travel down for Christmas if your family was on the mainland.”

The somewhat late establishment of an airport on Svalbard was partly due to Norway’s efforts to keep the archipelago out of “big politics.” Svalbard’s unique territorial status, coupled with the Russian presence on the archipelago and the provision in the Svalbard Treaty declaring it a demilitarized zone, necessitates careful consideration of all activities on the archipelago in light of their potential geopolitical ramifications. Russian authorities considered a Norwegian airport on Svalbard part of NATO’s expansion in the North and thus in conflict with the Treaty, and only agreed to the construction of a strictly civilian airport after significant political complications. For young Magnus, who was living with his family in Svalbard, one of the main positive effects of the opening of the airport was the change in diet. “After the airport was built, we got fresh vegetables and fish. You’d have placed an order at Provianten [the food supply warehouse – there was no store selling food at the time] for some kilos of fish and liver, and then they delivered it to you in the morning and mother could make a great dinner.”

The normalization of Longyearbyen during the 1970s laid the foundations for even greater societal transformations during the 1990s and early 2000s. The economy was diversified as tourism and research/education were introduced as economic pillars in addition to mining, and the Norwegian state invested heavily in Longyearbyen’s community development. Societal services were transferred from the coal mining company to the local government Longyearbyen Lokalstyre, operating much like a municipality on the mainland, and local democracy was established. In an editorial in the local newspaper Svalbardposten, former editor Birger Amundsen in 2007 asserted that Longyearbyen had entered a new era, with a record-high population of 2000, indicating growth and wellbeing. The “slumber time of Svalbard is definitely over,” he wrote. “For many it ended the day the first airplane landed on Hotellneset [the location of the airport] a little over 30 years ago.” Throughout the 2000s, the tourism industry in Longyearbyen started flourishing and the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), which had opened its campus in 1993, had become a well-established Arctic research hub. These economic changes, in combination with accelerating global mobility and the archipelago being visa-free and outside of Schengen due to the Svalbard Treaty, resulted in an increasingly international population.

Today, Magnus makes his living as a tourist guide, conveying the rich history of Longyearbyen to people from all over the world, attracted by the allure of the Arctic. Longyearbyen is now one of the most easily accessible High Arctic destinations, reachable via several daily direct flights from Oslo and Tromsø. This connectivity is a precondition for the economic and societal changes Longyearbyen is currently undergoing. Coal mining is being phased out, and the growth in the international and seasonal sectors of tourism and research/education has resulted in a cosmopolitan, dynamic, and transient community (almost 40% of the population comes from over 50 different countries and the annual turnover rate is 25%). Simultaneously, the Svalbard environment is transforming due to alarming climatic change and human pressure, and environmental regulations are being tightened. Locally, people are starting to notice the symptoms of a warming climate, such as melting glaciers and disappearing sea ice, and of “over-tourism,” questioning not only the constant influx of tourists but also the sustainability of their own (mobile) lifestyle within a changing Arctic. Due to its location, aviation is the only plausible means of transportation even for people with “flight shame,” and the occasionally empty vegetable shelves or the lack of milk in the local supermarket are reminders that everything in Svalbard is imported from far away. Although the airport is rarely thematized in these reflections, transportation infrastructure is likely to play an important role in future discussions about “sustainability” in Longyearbyen and other Arctic settlements in the era of the Anthropocene.

Please login to post a comment...