For Whom Do the Sleigh Bells Toll? Unwrapping Santa’s Arctic Infrastructures

By Ria-Maria Adams, Alexandra Meyer & Mia Bennett

According to popular belief, Santa Claus operates with a flying sleigh, pulled by reindeer – including one with a red nose. This means of transport allows him to access every corner of the world, no matter how remote and disconnected, needing only a rooftop or a small clearing in order to arrive and swiftly deliver his gifts. While many children believe that Santa’s home is in the North Pole, in fact, he resides in many locations throughout the European and North American Arctic, if the claims of tourism boards from Alaska to Finland are to be believed.

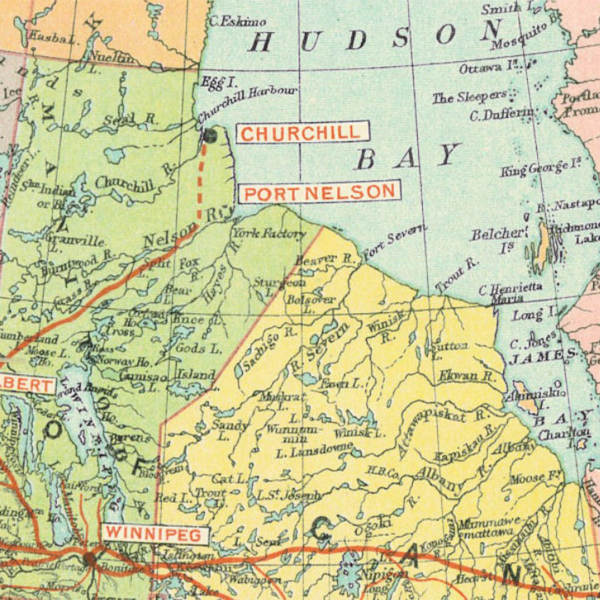

While Arctic infrastructure such as new runways, railroads, and airports captures international headlines, the structures and services that support Santa Claus’ annual journey fly under the radar. His infrastructural footprint extends from North Pole, Alaska to Rovaniemi, Finland, encompassing designations like Santa’s “official hometown,” “secret hideaway,” and “Santa’s house,” along with his “official mailing box” and workshop in the northernmost permanently inhabited town of Longyearbyen (Svalbard, Norway). Although we all stopped believing in Santa as children, our fieldwork in the Arctic has revealed to us how the myth has in fact become a local infrastructural reality. With tens of thousands of visitors drawn each year to meet Old St. Nick in person, tourism organizations, businesses, and local governments are increasingly capitalizing on the magic of the white-bearded gift-bearer. This raises questions about how the figure of Santa Claus has managed to establish and make use of northern infrastructure, much of which sits on predominantly Indigenous lands, across the Arctic.

The small town of North Pole is located around 20 kilometres southeast from Fairbanks, Alaska on the Richardson Highway. Despite its name, the city of 2,200 people is about 2,700 km south of the Earth’s geographic North Pole and about 200 km south of the Arctic Circle. North Pole started out as a homestead along the Richardson Highway – Alaska’s first long-distance, all-weather road infrastructure project, which transformed a dirt trail into a road suitable for automobiles in the 1920s. In 1944, a development company gave the town its iconic name in the hopes of attracting a toy manufacturer seeking to claim a “Made in the North Pole” designation for its products. While such a toy factory never manifested, in 1952, a store called “Santa Claus House” opened, selling dry goods and services for people driving along the Richardson Highway. By the 1970s, however, the merchant began selling Christmas items, helping to put North Pole, Alaska on the global Santa Claus map. This switch was fortuitous and has helped the town withstand the rerouting of the Richardson Highway away from its doorstep in 1972 and the closure of the last of its two oil refineries in 2014, which had brought rail tank traffic on the Alaska Railroad. Although the heavy-duty hydrocarbon infrastructure and the military-built wagon train that once supported freight movement from gold mines are now obsolete, the town instead houses the world’s largest fiberglass statue of Santa. Today, visitors stop by to take a picture with the giant Santa and his house at the site of the imaginary “North Pole”. For 70 years, the family-run business of Santa Claus House has attracted millions of visitors from around the world to the Alaskan Interior, proving Santa’s magic be more durable than state-led interventions.

On the other side of the Arctic in Finnish Lapland, Rovaniemi, the region’s capital, claims to be the “Official Home of Santa Claus”, and the city has licensed this trademark. Indeed, the local government has managed to successfully promote Finnish Lapland as the “true” home of Santa since the Finnish Tourism Board established a working group in 1984. That same year, the governor of Lapland declared the province as “Santa Claus Land”. The arrival of the Concorde supersonic airplane from Heathrow to Rovaniemi generated substantial media attention. The anticipation of the first Concorde was so great that a reported 20,000 locals turned up to witness the jet’s landing. In the late 1980s, early 1990s it became a popular daytrip from England, with the two-hour flight allowing families to spend eight hours on the snowy ground before flying home. The notion that a supersonic jet was required to reach “Santa’s hometown” suggested that the Arctic was perceived as a remote location. In 1985, Santa Claus Village, a theme park including a post office, hotels, restaurants and shops, opened its gates for visitors as the ultimate Christmas destination. The holiday village sits directly on the Arctic Circle at 66°30′N, merely three kilometers from Rovaniemi airport, ensuring a swift journey for tourists who wish to be transported into an imaginary world. Today, almost 40 years later, Visit Finland, the national destination management organization, still promotes Santa as “a jolly fellow and an ambassador of goodwill from Lapland”. Demonstrating the allure of strategic marketing, this season will welcome 20 direct flights from European destinations to Rovaniemi.

Santa’s third home (or remote work location, depending on your perspective) is Longyearbyen, Svalbard, which brands itself as “the world’s northernmost town.” According to Visit Svalbard, even if Santa might not live here year-round, Longyearbyen’s relative closeness to the geographic North Pole means that letters sent to him here will arrive first. It is thus unsurprising that this place is a communication hub for Santa. As part of an initiative to attract Asian tourists to Longyearbyen, a business operator from Hong Kong unveiled a nearly ten-meter-tall, bright red mailbox near the center of town in 2013. With the “world’s largest Santa’s mailbox,” the initiator hoped to market Longyearbyen as the real “Santa Claus Town.” Local officials, however, were not too pleased with this unexpected and controversial gift, and the mailbox had to be taken down in 2017 due to permit issues.

While this might have been a blow to the business operator’s expansion strategy, it did not prevent Santa from receiving his mail. According to local folklore, Santa’s “official” mailbox is, in fact, located at the base of the mountain Gruvefjellet at the now closed Number 2B coal mine, which is also called the “Santa mine”. According to local legend (and when he is not busy welcoming tourists in Rovaniemi or selling souvenirs to travelers in Alaska), Santa spends the month of December in this mine, preparing gifts – and lumps of coal for naughty children. Every year during the First Sunday of Advent, locals light torches and process to the mailbox, singing Christmas carols and posting their wish lists. Alaska Dispatch provides further support to claims associating the mythical figure with Svalbard. As Santa’s preferred means of transportation is a reindeer-pulled sleigh, the small Svalbard reindeer (R.t. platyrhynchus) are the only ones that realistically can land atop a roof in order to deliver gifts through a chimney.

Swedish Lapland wants to tap into the Santa business as well. The mining town of Kiruna is increasingly becoming a tourist destination, offering holiday packages like “Santa’s Secret Hideaway.” Customers can choose between two, four, or eight-hour tours with “Santa Claus and his wife,” who await their guests with “warm mulled wine or warm lingonberry drinks” (Nordic Marketing, 2023). While we haven’t found the exact location of Santa’s Secret Hideaway in Kiruna yet, we met Santa himself while walking in front of the town’s newly built city hall during a visit in December 2022. Santa Claus, too, will need to get used to his new surroundings. About a third of the town is being relocated a few kilometers south of the city’s original location to allow the LKAB mine to continue to expand underground. LKAB has also identified rare earth elements nearby, which are rising in demand due to the green transition. Santa may be known for carrying (Norwegian) lumps of coal, but Swedish iron ore and rare earth elements may soon be filling his sack, too.

While different towns and places claim to be the hometown of Santa, his infrastructural traces indicate that he is a busy commuter. His multiple homes and work locations even predate the pandemic-induced trend towards heightened mobility. Our examples demonstrate that although his preferred means of transportation – reindeer – does not necessitate any road, runway or harbour, carbon-intensive infrastructure still plays a pivotal role in Santa’s world. A comprehensive network of highways, airports, and roads lays the essential groundwork for Old Saint Nick to operate seamlessly and draw in visitors from all over the world. Whether considering his secret hideouts or commercialized visitors’ centres, accessibility emerges as the linchpin for spreading the holiday magic.

Santa’s growing imprint across the Arctic, however, is not all fun and games. The promotion of the imaginary figure of Santa Claus and other related processes like the Disneyfication of the Arctic have and continue to cause harm to Indigenous cultures and ways of life. Santa’s main traffic arteries are encroaching on reindeer grazing areas. New (tourist) infrastructure is typically built to satisfy the imagination of tourists rather than to recognize and carefully co-create more sustainable tourism practices with local Indigenous communities and governments. Once confined to Western imaginaries, Santa Claus is now materializing across the Arctic, leaving much more than ashy footprints from fireplaces and the snowy imprints of the hooves of eight tiny reindeer. Unless rigorous consultation and Free, Prior, and Informed Consent is practiced in advance of any expansion of Santa’s infrastructure, the sound of sleigh bells calling in the falling snow may be an alarm for those who have called the region home long before he arrived.