The New Subsea Tunnel to Sandoy, Faroe Islands: From the Periphery to the Centre?

By Alexis Sancho Reinoso

This post is inspired by my storymap entitled “I walked over the Atlantic… or: how a small fishing nation manages to build a world-class road network” (October 2023).

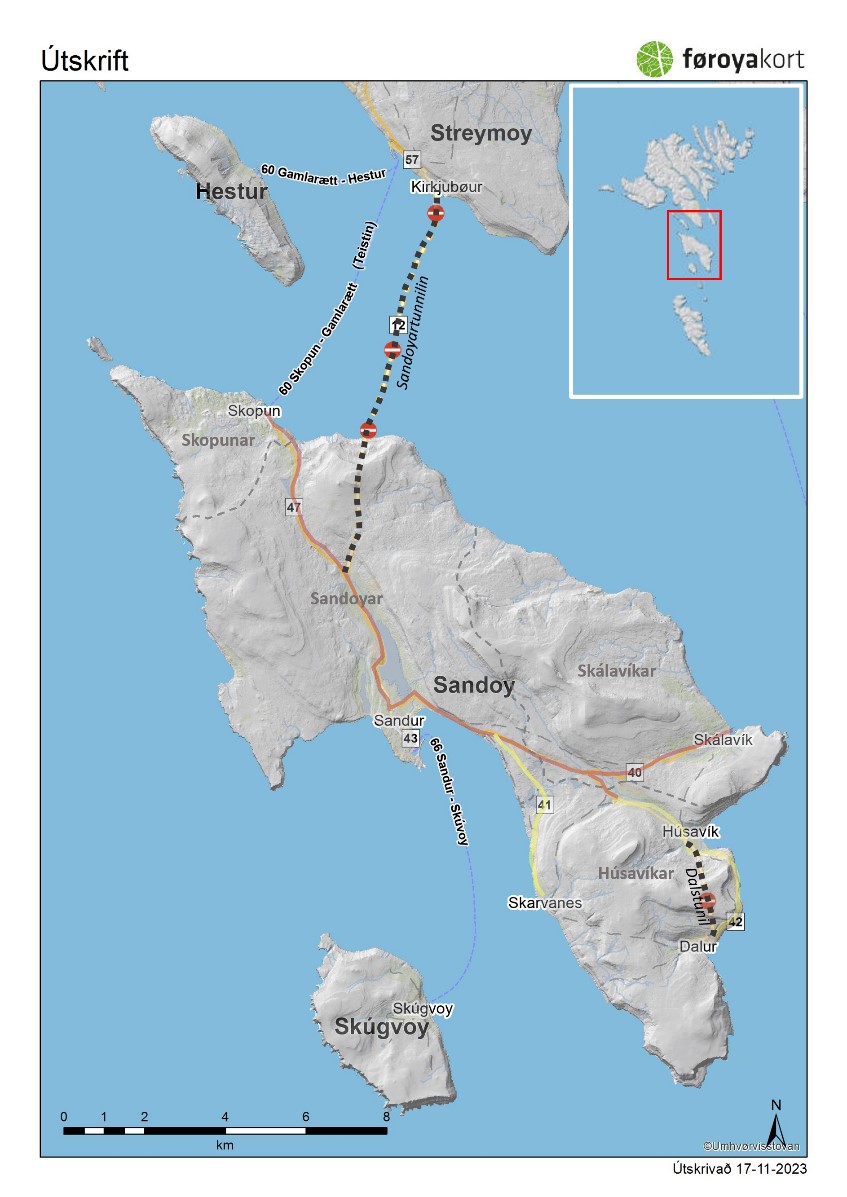

Timely before Christmas, the Faroe Islands’ fourth subsea tunnel connecting the islands of Streymoy and Sandoy will be inaugurated. Since the 1970s, most of the islands of the archipelago have been connected with roads; first with bridges and causeways; more recently, with subsea tunnels. These so-called “fixed links” are gradually replacing ferry connections in the Faroe Islands. As this happens, life on the small islands is changing. During my stay in the Faroes last October, I decided to embark on the M/F Teistin ferry and to spend one day travelling around Sandoy before its towns and villages will be connected to the main road network.

The Teistin left the port of Gamlarætt in Streymoy and arrived at the port of Skopun (the isle’s second largest town; pop: 473) half an hour later. Upon the ferry’s arrival, the rush hour began: passengers were stepping in and out; cars burst into the town’s narrow streets; and the local grocery store got its delivery from the truck that had boarded in the same service I had. But things are going to change very soon in Skopun. In the outskirts, freshly developed plots of land are ready to host newcomers, who will be attracted by lower property prices and by regular and convenient road connection to the capital of Tórshavn. The port will lose its vitality, and the ferry won’t determine the rhythm of life any more.

I then headed south to Sandur, the largest settlement on the island (pop: 535). I didn’t find the same bustle there as I had seen in Skopun harbor. “This is a small village and I don’t think life is going to change so much,” said the woman who served me a hot dog in a small corner shop after I asked her about the new tunnel. Yet, when I mentioned the new developments in Skopun, she admitted that the municipal council is doing an inventory of the land plots that can potentially host new housing. Either way, Monday morning doesn’t seem to be the busiest time of the week in Sandur, neither in the town centre nor in the harbour. So, I decided to continue my trip to other villages.

Drilling an 11-km-long subsea tunnel for a 1,300-inhabitant-island might seem pretty courageous (or perhaps reckless) from an outsider perspective. But things seem to be different on the Faroe Islands. My next stop was Dalur (pop.: 33), which is located in one of the southernmost bays in Sandoy. This village can only be reached through a narrow road along the steep coastline offering breath-taking views to the open ocean. Yet, a new tunnel is under construction connecting Dalur with Húsavík (population: 58). After years of delay and subsequent protests, the tunnel construction site seems to have received some tailwind: the northern mouth of the gallery in Húsavík was full of trucks transporting debris.

My last stop was Skálavík (pop: 134). First, I strolled to the harbour, where I noticed some maintenance work that was being carried out at the pier. Then, I walked uphill towards the cliffs, and I was surprised when I came across a huge area of gravel right next to the shore that looked like an abandoned site. Bakkafrost, the largest fishing company of the country, planned a salmon breeding plant in Skálavík. However, the project’s future is now uncertain after the government passed a proposal increasing revenue tax on the salmon farming industry. Back in the town centre, I had time to enjoy a cup of tea at the local bus station, a cosy rest stop decorated with a nice collection of old pictures. With no opportunity to chat with anyone, I had to content myself with browsing a hard copy of the Dalur tunnel project that was lying on one of the tables.

Sandoy is the fifth largest isle of the Faroese archipelago (111.2 sq. km), but it currently counts only 2.3% of the country’s population (ca. 54,000 inhabs.) and has a population density of just 11 inhabitants per sq. km. In the EU, regions below the threshold of 12.5 are considered as “sparsely populated.” Within the archipelago, there is no doubt that it can be considered as peripheral.

Peripheries are places where resources of any kind are extracted in favour of centres (or “the core”), where accumulation takes place. Yet, in reality, most places can’t be classified in either of these two categories. One of the factors that make things trickier is transport infrastructure. In the Faroe Islands, roads and tunnels are usually perceived by the so-called “outer islands” as the means to escape from a peripheral status. However, fixed links can become a double-edged sword: Certainly, they make it easier for people to get to Tórshavn while living outside the capital. But: the whole social life might move to the centre at the expense of the periphery, which very often turns into residential areas lacking schools, doctors, shops and spaces where you can meet a friend. This is the challenge Sandoy will have to address on its path towards becoming part of “the centre.”

Please login to post a comment...