Plenty of Land, Nowhere to Live: Housing as a Limited Resource in Arctic Communities

By Ria-Maria Adams and Katrin Schmid

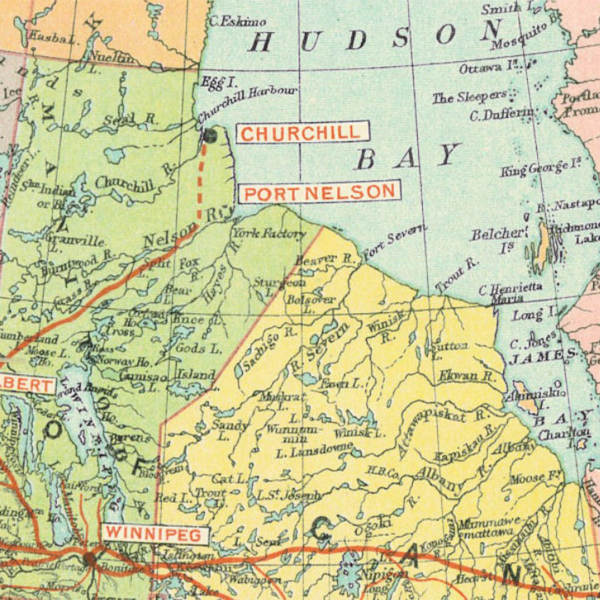

At first glance, northern Sweden’s Malmfälten region and Nunavut in Arctic Canada might seem worlds apart. While the Malmfälten region is defined by a few centralized company towns, Nunavut has 25 small, scattered communities. The Swedish towns of Kiruna and Gällivare are connected to the national power grid and to large-scale infrastructure such as railway, airports and roads. In contrast, Nunavut remains completely off-grid, reliant on diesel shipped up from southern Canadian ports. With no roads leading outside of the communities, airports and one deep-sea port create the main infrastructural hubs. Kiruna and Gällivare are seeing a gradual population decline, while Nunavut is experiencing steady growth. In Sweden, the state plays a dual role as both regulator and owner of the dominant mining company, LKAB, while in Canada, the state regulates but leaves extraction to private industry. There’s also a notable demographic contrast: in northern Sweden, the Indigenous Sámi are a minority; in Nunavut, Inuit are a clear majority, making up 85% of the territory’s population. These differences are significant and matter – but what’s equally striking are the shared challenges, especially when it comes to housing in the Arctic.

When a young mother from the community of Resolute Bay, Nunavut, was asked about the infrastructural challenges her town faces, her answer cut straight to the heart of the matter:

“Some people have a very hard time finding homes here. I’ve been waiting five years to get a house, and I’m finally getting one in November. I’ve been living with my mom. I think it’s just a lack of housing. That’s a big reason [why people move away].”

This sentiment is echoed thousands of kilometers away in northern Sweden, where residents in the mining towns of Gällivare and Kiruna find themselves caught in long queues for rental apartments.

Both Swedish mining towns are undergoing major transformations, largely funded by the state-owned mining giant LKAB. In Kiruna, the discovery of a new ore body beneath the town triggered a massive relocation – about a third of the city is being moved 4 kilometers east, a process that began in 2016 and will continue until 2035. In Gällivare, LKAB’s Malmberget mine is driving a similar shift, with large parts of Malmberget being integrated into Gällivare.

While mining companies are financing replacement buildings in areas affected by extraction, they often argue that building new, additional housing beyond that is not their responsibility. Municipalities, meanwhile, are tasked with providing permits and basic infrastructure, while the actual construction falls to private investors, housing companies, or individuals. But in these Arctic towns, developers are hesitant. In Sweden, the rise of automation in mining leads some to question how long the current industrial boom will last. With the prospect of resource depletion within perhaps 20 to 40 years, many housing companies prefer to invest elsewhere – in places where a quicker, safer return on investment seems more certain. In Nunavut, mines – like Baffinland’s Mary River iron ore mine – are the biggest contributor to the territorial gross domestic product (GDP) other than the administrative sector, yet their role in sustainable community development remains meager.

Canada’s approach to northern housing is complex, particularly in Nunavut, where the public government (Government of Nunavut, or GN) operates alongside Inuit organizations like Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI). As former Senator Glenn Patterson noted, overlapping funding streams from the federal government and Inuit organizations can create redundancies and confusion. Public housing is allocated through a territorial point-rating system in Nunavut. Points are awarded for things like overcrowding or escaping domestic violence. But residents often don’t know where they stand. One woman in Iqaluit explained:

“I’ve applied for a spot at the women’s shelter for years… I can get points every time I apply, so I put in an application every time I get income support.”

The lack of clarity in the system leaves people in limbo. In Pond Inlet, a couple with four children rented a single room while waiting for public housing. Another resident summed it up bluntly: “To get a house you need to have, like, five kids, or you’re practically homeless.”

While Swedish Arctic towns face waiting times between two and eight years for housing, the quality of infrastructure and housing is high standard compared to the Canadian examples we studied, where poor housing conditions are widespread. Yet in both regions, demand far outpaces supply, and even newly built apartments fail to address the broader shortage of adequate housing. Community projects are also suffering, with many stalled due to soaring construction costs. One resident of Gällivare described their frustration over a delayed project:

“In the middle of the city center, there’s this huge multicenter project that should have been finished by now. But they ran out of money. Nothing has happened for a long time, and who knows if they’ll ever complete it. Building costs have skyrocketed in the past few years, and the promised funding just isn’t enough to finish it as originally planned.”

A common challenge in both Malmfälten and Nunavut is the shortage of skilled labor – and, more fundamentally, the lack of housing to accommodate that labor. Nunavut’s population is the fastest growing in the country, yet limited local training opportunities mean that most trades workers and mining employees are flown in from the South, leading companies to invest in housing at remote mining camps rather than in long-term accommodation within communities. A similar pattern is emerging in northern Sweden. As one resident in Gällivare put it:

“It’s really expensive. Hotel prices are high, and even if a company has the money, there’s no space to accommodate the workers.”

Researchers like us experience this problem firsthand too: finding accommodation can be challenging, and when something is available, it’s often expensive or the quality doesn’t match the high prices paid.

In Nunavut, the logistical cost of transporting materials by ship or air – combined with limited energy and fuel infrastructure – creates massive, and expensive obstacles. A new initiative, Nunavut3000, aims to build 3,000 homes by 2030, but residents are skeptical: “If Nunavut3000 actually wants to build 3,000 homes by 2030, some of the communities will have to build second or third fuel tanks,” one resident said at a dinner in Iqaluit. “And that’s construction too.” Without enough diesel to run equipment or enough space on cargo ships to carry materials, even the most ambitious plans remain vulnerable to delay and inflation. In contrast, Sweden’s North is fully integrated into national logistics networks. When projects do move forward, they happen fast. But the costs, both of labor and materials, remain a major hurdle in a profit-oriented economy.

Faced with persistent housing shortages, residents in both regions have developed their own ways to cope. In Nunavut, many people remain in overcrowded family homes or might delay employment that could disqualify them from subsidized housing. Nunavut’s housing disparities also reflect settler colonial realities: Many residents feel that Qallunaat (non-Inuit) workers receive preferential treatment in housing allocation: “They [Southerners] get a house, furniture, even a truck sometimes,” one woman in Resolute Bay said. “[There are] just a lot of people that have to get flown in; and then they take housing.” In Sweden, some workers live in caravans on campgrounds or in cottages and houses located outside the towns: “People post on Facebook groups that they want to move and work here,” said a Gällivare resident. “But there is almost no chance to find any place to live.”

Despite the frustration, there are some promising projects and developments taking place. In both Gällivare and Kiruna, new schools, municipal buildings, shops, restaurants, offices, and sports facilities have already been completed with support from LKAB – and are widely appreciated by the local residents. In addition, a new hotel complex at the Dundret mountain area in Gällivare is currently at the planning stage. In Nunavut, community-focused projects like those proposed by Inuit-owned construction companies like ArchTech could help ensure that new housing initiatives benefit residents directly – if they are properly supported. Yet, in both contexts, optimism is often tempered by realism.

As one resident in Iqaluit put it, solving the housing crisis in the North isn’t just about bricks and mortar – it’s about governance, logistics, funding, and above all, people. After all, housing is not merely infrastructure; it’s the foundation of daily life, memory, and belonging. But without reliable and affordable transport infrastructure to move materials, access communities, and support construction, even the best housing plans remain up in the air.

Please login to post a comment...