Why Do Infrastructures Matter? Some Remarks from the Conference of the Finnish Anthropological Society in Rovaniemi, Finland

By Alexis Sancho Reinoso

The iron bridge in Rovaniemi affords rail and road traffic of people and goods, including the crossing of the frozen Kemijoki River by cyclists and pedestrians. Photo by Alexis Sancho Reinoso.

These lines summarize a series of personal thoughts from a geographer who had the opportunity to participate in the Biannual Conference of the Finnish Anthropological Society. The event took place on March 21-23 in Rovaniemi, the capital of Finnish Lapland, and it was incredibly well organized by the Anthropology Research Team at the Arctic Centre under the motto “relations and beyond”. The conference gathered about 300 participants, including three very prominent British social anthropologists as keynote speakers, namely Piers Vitebsky, Marilyn Strathern and Tim Ingold.

In this blog post, I’d like to address the fact that infrastructures aren’t just mere technical objects that are used by people. As a matter of fact, there is a number of implications over space, time, and people around infrastructures. For instance, they can be understood as complex systems of relations between human beings and physical objects under given conditions of power, uncertainty, and vested interests.

Marilyn Strathern’s keynote was held in the Fellman Hall at the University of Lapland campus. Photo by Alexis Sancho Reinoso.

To do so, I’ll focus on one particular conference panel entitled “Infrastructures as Relations”, which was organized by the InfraNorth members Ria-Maria Adams and Philipp Budka. The panel was divided into three sessions and included twelve papers that provided an extraordinary diversity of thematic and geographical foci. I’ll briefly discuss six topics or dimensions that, in my opinion, reflect the role of infrastructures in a changing world.

Infrastructures can be understood as manifestations of injustice and/or inequality when it comes to e.g. explosive urban growth, as the example of the informal settlements in Windhoek presented by Lalli Metsola shows. In the slums of the Namibian capital city, locals are forced to engage with precarious infrastructure by relying on improvisation and social ties. Another example came from Lapland, where Sámi people struggle with extensive wind power projects that might be seen as a kind of “energetic neo-colonialism”, according to Anna Varfolomeeva’s paper.

Infrastructures are used to exercise power and control, as Annika Pohl Harrison argued in her paper about the fence dividing the EU and Schengen countries of Denmark and Germany. The fence was erected by the former country with the pretext of protecting national pig livestock from diseases wild boars from the South might introduce. Infrastructures can also be used for subjugation purposes, even if the official discourses strive for strengthen linkages between countries, as Phill Wilcox’s paper about the railroad connecting China with Laos suggests. Control can be exercised over citizens in form of perverse and arbitrary bureaucratic procedures as well, as the example brought up by Ali Mohsin shows. In the city of Lahore (Pakistan), women are forced to cope in vain with dysfunctional biometric recognition infrastructure.

Discussion during the panel “Infrastructures as Relations” at the Arktikum’s Polarium theater. Photo by Alexis Sancho Reinoso.

Infrastructures can become the expression of collapse (from the local to the global scale). Susanna Gartler reported on local efforts to cope with coastal erosion due to permafrost thaw in the Canadian Arctic. Permafrost (as well as sea ice) is often considered as a critical infrastructure that literally sustains human settlements and other infrastructures. As a matter of fact, permafrost thaw confronts the entire humanity with global catastrophic consequences.

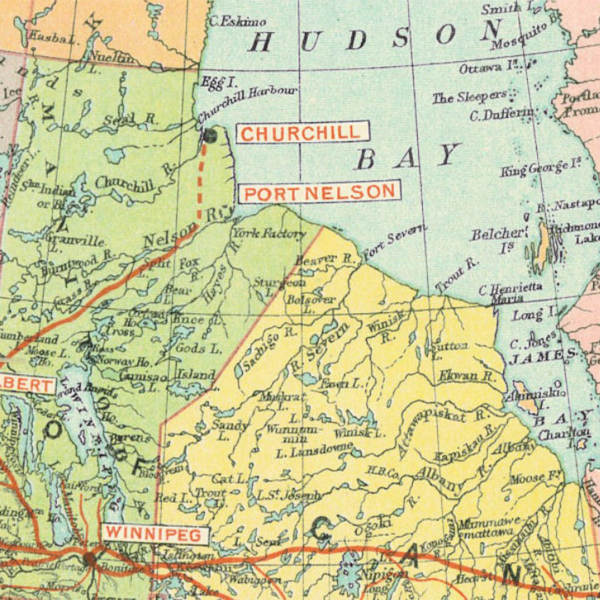

Infrastructure can suffer disruptions and, therefore, lead to profound societal changes that put community resilience degree to the test. Yet, the temporary collapse or malfunction of an infrastructure can be taken as an opportunity to re-think and/or restart after a disruption episode, as the example of the town of Churchill (Manitoba, Canada) shows. Philipp Budka explained what happened there after an 18-month railroad disconnection due to the flooding of railway tracks in 2017. Locals have started initiatives related to sustainability and food sovereignty, such as the production of vegetables. In Poland, spa towns (Zdroj) struggle to reposition themselves as wellness tourist destinations by taking advantage of the existing facilities that were privatized after the political turn into a market economy, as Hubert Wierciński reported.

Infrastructures can become identity markers or makers. In her paper presentation, Teresa Komu informed about miners’ life conditions in Europe’s deepest mine of Pyhäsalmi, Finland. Her first-hand experience showed how human life is interlinked with machines in this underworld. Therefore, humans can be seen as part of an infrastructure, as also Otto Habeck argued in his presentation on the role telephone operators used to play in times prior to mobile phones. Today, engagement with communication infrastructure and their devices is likewise indisputable, yet not so self-evident due to the ubiquitous use of telecommunication. Jolynna Sinanan demonstrated this with a paper on digital infrastructure as a human-object meshwork, which decisively contributes to the visual narratives of climbing the Mount Everest.

I’ve left my contribution until last, and this was no coincidence. My own paper was a meta-reflection about why we need comparison when doing infrastructure research, regardless of the discipline (if this issue is still relevant in a wold of emerging complexity that can hardly be tackled from a compartmentalized approach). All we need is to find a common ground to be able to compare: in the end, this blog post is nothing but an attempt to compare across places and topics. And just because of professional bias, I compiled a visualization of all the contributions from the panel in a story map. You can access the map by clicking on the screenshot below. Enjoy the virtual journey!