Not Building Roads in Alaska: The Ambler Road Controversy in Context

By Peter Schweitzer

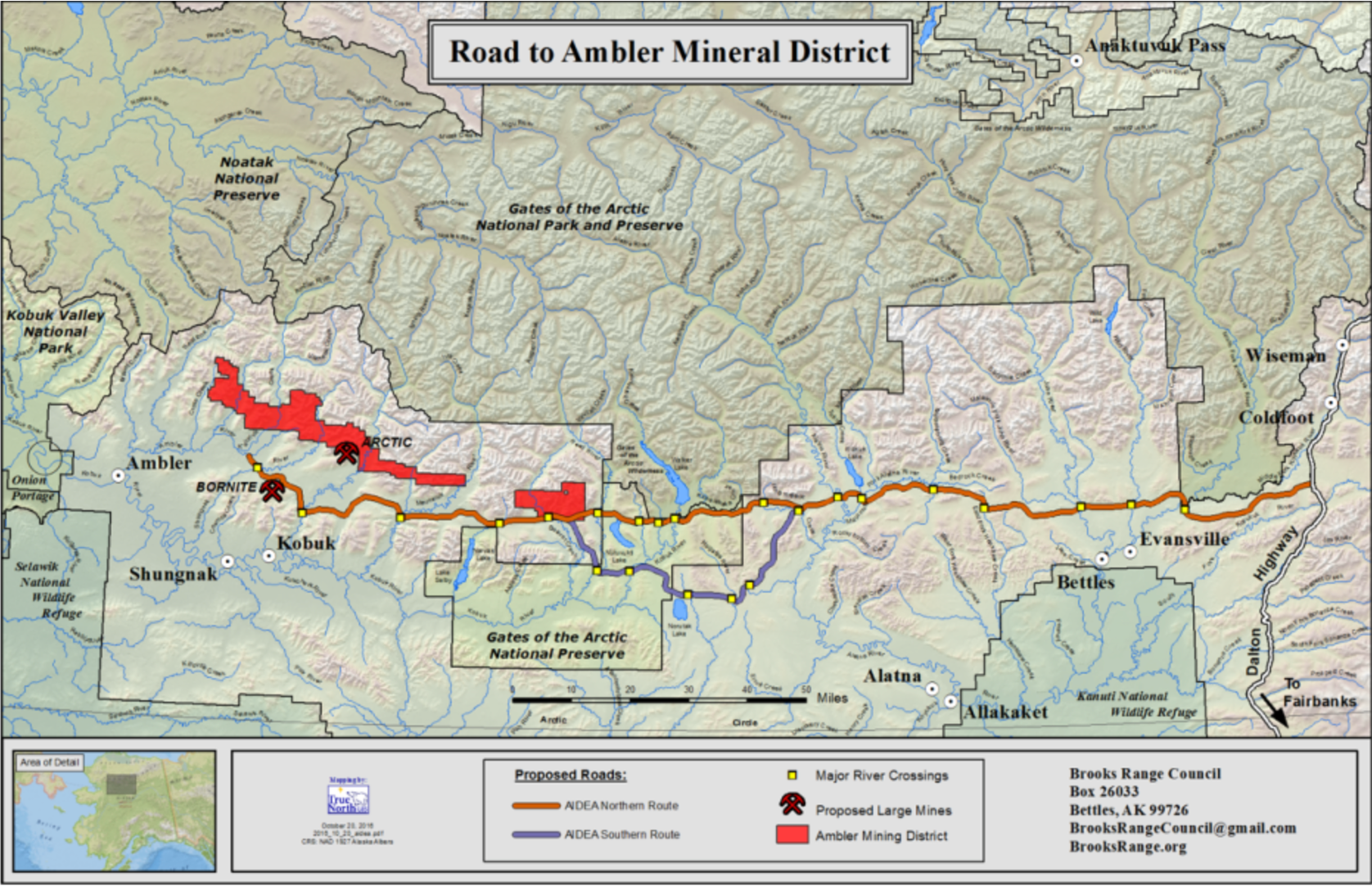

In April 2024, the Biden administration moved to block the proposed Ambler Road, a 211-mile transport infrastructure that would allow access to valuable mineral deposits in Northwest Alaska. This decision was based on the results of a “supplemental environmental impact statement” conducted by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). In June 2024, the BLM published a “record of decision” regarding the Ambler Road proposal, denying the right-of-way application and selecting a “no action alternative,” which is basically a no-road option.

While an outside observer might conclude that the issue – a contested proposal to build a road through an area of high value for conservationists and for subsistence users alike – is thereby off the table, followers of Alaskan and U.S. politics know better. First, the November 2024 U.S. Presidential elections will result in a new administration and, depending on which candidate/party wins, the Ambler Road issue might be taken up again – or not. Second, notwithstanding the decisions by the Biden administration and the BLM, the controversy continues: as of July 2024, Alaskan newspapers continue to contain opinion pieces pro and con the Ambler Road. Finally, controversies over building or not building roads are nothing new in the recent history of Alaska; this short commentary will focus on the latter aspect.

Talks about building new roads – and in some cases railroads – began soon after the U.S. took colonial possession of Alaska in 1867. While the Russian chapter of Alaskan history, as well as the first few decades of U.S. possession, were focused on Southeast and South Alaska, and thus on coastal areas and maritime transport, the discovery of gold and the resulting rush for this mineral in the Canadian Klondike and the Alaskan Interior necessitated reliable overland travel routes. Likewise, the role of Alaska during World War II (from the U.S. Lend-Lease program to the Soviet Union to the Japanese attacks on the Aleutian Islands) called for even more transport infrastructure development, including the construction of the famous Alaska Highway connecting Alaska with the continental U.S. The large resource extraction boom following the discovery and exploitation of oil on Alaska’s North Slope, and the construction of the Trans-Alaska-Pipeline, led to building a “Haul Road” parallel to the future pipeline in the area north of Fairbanks. This road, now known as Dalton Highway, was completed in 1974, originally owned and controlled by the pipeline company but “gifted” to the state in 1979. The road was partially opened to the public in 1981 and fully in 1994. One of my conversation partners in Anchorage remarked last July, “I came here in 1977 and they haven’t built a road since.”

The proposed Ambler Road would connect via the Dalton Highway to the Alaska road system. This is not the only connection between these two roads. The above-mentioned “opening” of the Dalton Highway to the general public is an important argument against the Ambler Road, which is supposed to be used for industrial purposes only and not open to the public. The precedent of the Dalton Highway, however, where full public access was the result of a court case, is an additional argument for critics of the Ambler Road. The main arguments against this are, however, based on environmental and cultural concerns. The Ambler Road would cross a section of the Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve and would provide motorized access to areas important for the subsistence of local residents. For the proponents, on the other hand, some of whom are local/Indigenous residents, the prospect of economic development and cheaper grocery prices prevail.

Among the many unrealized Alaskan road projects of the last half century, a prime example is the plan to build a road between Nome and Fairbanks. While several governors had written this and similar projects into their economic development agendas, Nome isn’t connected to the Alaskan road system and will not be in the foreseeable future. While conducting fieldwork on the proposed seaport expansion in Nome in 2022 and 2023, my colleague Olga Povoroznyuk and I asked a number of local residents, whether they would support a road to Fairbanks. With very few exceptions, people opposed a road and considered it highly unlikely given the price tag of building and maintaining such a road. The main reason for their opposition to the road was resource competition, as local residents feared that Alaskan urbanites from Fairbanks and Anchorage would encroach on their subsistence resources.

“Easy to Start, Impossible to Finish” was the heading under which Lois Epstein, an Anchorage-based civil and environmental engineer, wrote a number of detailed reports for The Wilderness Society, where she was working at the time, about Alaskan transportation infrastructure projects, including the Ambler Road (e.g., Epstein 2016) [1]. The reports criticize the tendency of politicians and bureaucrats, who have millions but not the necessary billions at their disposal, to spend significant amounts of money on feasibility studies, while knowing that there isn’t enough money to actually build expensive roads or other infrastructure objects.

While the eventual fate of the Ambler Road project is subject to the uncertainties of U.S. politics, it is highly unlikely that the road will be built in the foreseeable future. The deciding reasons against a road will most likely not be local protests or environmental concerns but the fact that building and maintaining a road in the wilderness of Northwest Alaska is extremely expensive. This means that the economic value of the mineral resources of the Ambler Mining District, would need to rise dramatically – and the price for mining them diminish – before this project would be realized. This shows that decisions about transport infrastructures in Alaska and in other parts of the Arctic are determined by economic considerations of outside actors and not driven by the needs of local residents. For local residents who oppose infrastructure developments, the last half century has been positive insofar the dreams of economic boosters did not materialize and “not building roads” became the standard. The question is what will happen once another resource boom hits Alaska. Will local and environmental concerns, which are easy to pay lip service to during economic downturns, be overshadowed by the prospect of enormous profits (for some)?

[1] Epstein, Lois (2016). Easy to Start, Impossible to Finish IV: Despite budget troubles, Alaska continues to spend millions on questionable road, bridge and energy projects. Anchorage, Alaska: The Wilderness Society.