Light at the End of the Tunnel: Transport Infrastructures in the Faroe Islands

By Timothy Heleniak

I travelled to the Faroe Islands not to go hiking, view puffins, or take in a concert of Faroese music at the wonderful Nordic House. Rather, I ventured to the north Atlantic archipelago to study the decades-long transport infrastructure project of linking the islands together. Many of the infrastructure projects studied within the framework of Infranorth involve railroads and roads, which span hundreds of kilometres or ports and airports which are the locus of long-distance travel or goods transport. The development of transport infrastructure in the Faroe Islands is on a smaller scale and has a different focus with the main goal of facilitating mobility among the 18 islands.

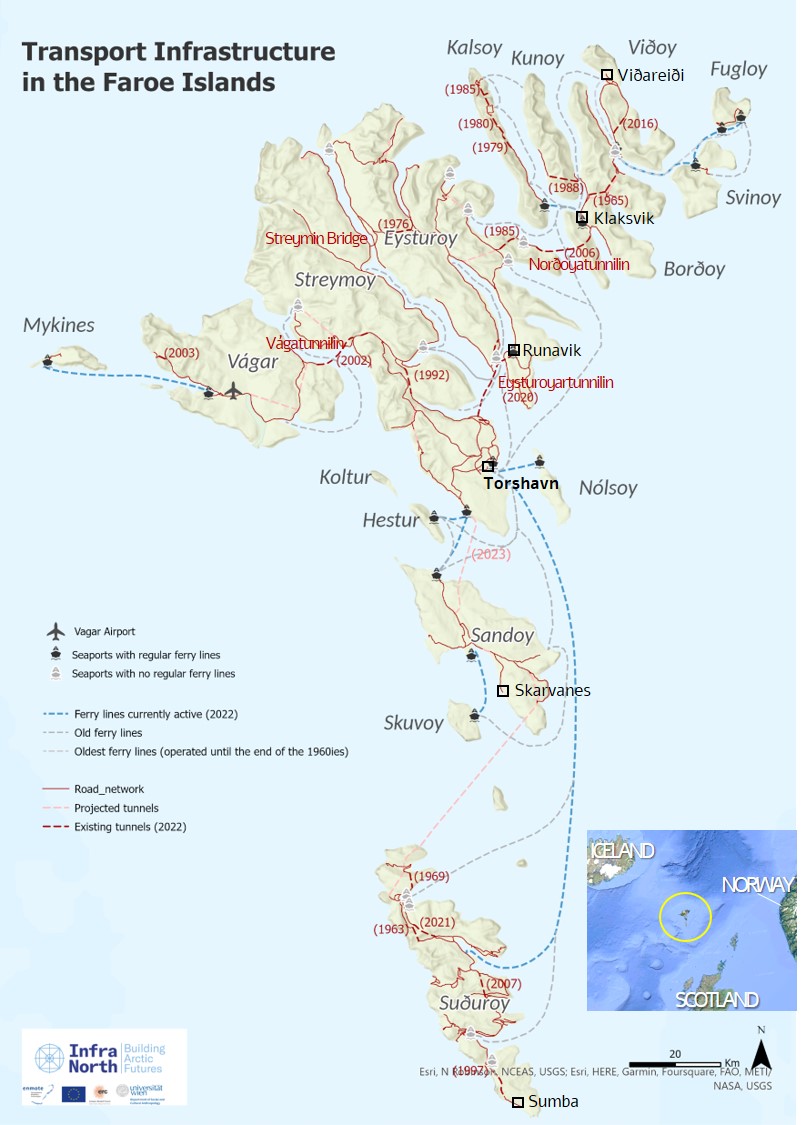

The Faroes are a small archipelago of 18 islands in the North Atlantic at 62 degrees north. It is an autonomous territory within the Danish kingdom. The total area is 1,396 km² and islands are quite mountainous with steep cliffs and little arable or flat land. The longest distance north-south is 118 kilometres and east-west is 79 kilometres. Nearly all population settlements are located along the coasts or in protected bays. The population is spread among 120 villages (or bygd). The airport is located on the island of Vágar. The capital and largest city of Tórshavn (population 13,969) is located on the island of Streymoy. Streymoy and the island to the east, Eysturoy, contain 70 percent of the population are often referred to as the ‘mainland’. To the northeast are a group of islands referred to as the northern islands as is the location of the second largest settlement, Klaksvík (population 5,033). To the immediate south is the sparsely populated Sandoy (population 1,224) and further south is Suðuroy (population 4,684). Of the 18 main islands, 17 are populated.

Part of the rationale behind improving transport infrastructure in the Faroes is the structural change in the economy. The economy was based on sheep farming until 1800s, the population was small, only 5,265 in 1801, and most of the population resided in small settlements. Fishing became important in the mid-nineteenth century and the population began to concentrate into larger towns with good harbours. More recently, there has been a relative decline in the fishing sector and growth of the service sector, including tourism, which now accounts for about 6 percent of GDP. With modernisation in fisheries, the population began a period of significant growth, tripling over the nineteenth century to 15,230 in 1901. There was a 9 percent population decline resulting from a crash in the fishing sector during the 1990s but a rebound since and the population now stands at its highest ever level, 54,167.

The transport infrastructure project in the Faroes began sixty years ago in 1963. At that time, the road system linking villages was quite limited and often involved walking or a harrowing drive over a mountain. The first tunnel was completed in 1963 linking two villages on Suðuroy. There are currently 21 tunnels in the Faroes including three subsea tunnels. In some places, the distance between islands is quite small and bridges can connect islands. There are three bridges including the Streymin Bridge, which connects Streymoy and Eysturoy (two of the three bridges are causeways). The Faroe’s only airport had been constructed by the British Army during WWII but was abandoned after the war and not reopened for civilian use until 1963. The first subsea tunnel, the Vágatunnilin, opened in 2002 linking the airport on Vágar to the capital of Tórshavn. What had been a three-hour plus trip, including a ferry crossing, was reduced to a 40-minute car or bus trip. With the opening of the subsea tunnel to the island of Sandoy in late 2023, 88 percent of the population will be connected to the national road system.

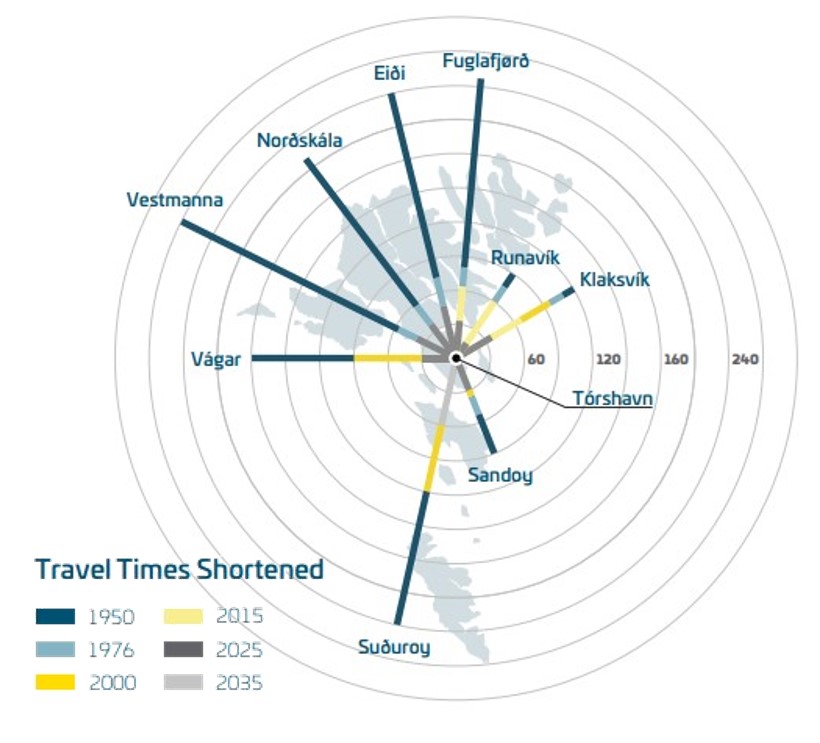

The transport plan envisions tying together the population with Tórshavn as the centre or downtown and the villages as suburbs within a one-hour drive. The goal has largely been accomplished as shown in the diagram which charts the reduction in commuter times with additional infrastructure. The trip from the most remote northern villages took three to four hours when a ferry and circuitous road trips was involved but with tunnels and improved roads, trips are now less than an hour. Even travel to Suðuroy, the southern-most island has been reduced from four to two hours with better ferries. Landsverk is the Faroese office of public works in charge of road and infrastructure construction. Most of the subsea tunnels are financed through loans with user fees collected to pay them off.

A good way to explore the transport infrastructure in the Faroes is to experience it by driving, so I rented a car. A few minutes north of Tórshavn, I drove through the new Eysturoyartunnilin. This features the world’s first underwater roundabout, which is quite eye-catching with shifting colours highlighting the artwork in the centre. This reduces travel time from Runavik and surrounding villages to Tórshavn from over an hour to just 15 minutes. After passing through the Norðoyatunnilin, within 40 minutes, I was in Klaksvík. Driving north, I reached Viðareiði (population 348), the northern-most settlement on the road system, now a little more than an hour’s drive from Tórshavn. I then backtracked and headed north to the village of Eiði, at the north end of Eysturoy. From that distant village, it was an easy 45-minute drive back to Tórshavn. There are no more than two-lane roads in the Faroes and even with an increase in the number of cars, there is little traffic, so that road trips are quite predictable – at least in good weather. Of the 21 tunnels, nine are two-lane and 12 are one-lane. The one-lane tunnels are well regulated with stop lights controlling entry, but some still provide an exciting driving experience as they are quite narrow and long.

One day, I took the two-hour ferry ride to Suðuroy, the southernmost island. From January 2024, this will be the only large island not connected to the national road network. While a speculator ride for tourists, it makes for a long trip for commuters to Tórshavn, though there are those who make the trip on a daily or periodic basis. The ferry, M/F Smyril docks in Suðuroy at night and departs in the mornings. The distance to Tórshavn has resulted in Suðuroy operating as a separate labour market, with higher unemployment. A pilot study has been conducted to examine options for linking Suðuroy with the mainland. The options include keeping the current ferry, a new ferry from Skarvanes on southern Sandoy, three tunnel options from Sandoy including a railway tunnel. At 26 kms, the proposed tunnel would be more than double the length of the tunnel to Eysturoy. Social, economic, environmental, and financial factors of all options are being factored into the decision.

The Nordic model is underpinned by a social contract to provide public services regardless of place of residence. This is a challenge in rural areas but the construction of the road network in the Faroes helps to achieve this goal by linking communities and creating a more equal demographic structure. This long-term transport infrastructure project of connecting the islands certainly seems to have played a role in sustaining Faroese communities. While some of the outer lying communities have declined slightly in population size, their demographic structure has improved with larger shares in the working ages and more balanced sex ratios. In the absence of the system of bridges and tunnels, it is likely that many of the remote islands would have lost almost their entire populations through out-migration to Tórshavn or abroad. One drawback of this transport network is that with less public transport, the country has become very car dependent – not unlike many other places in the world.

Please login to post a comment...