Ethnography Beyond the Case Study: InfraNorth Workshop on Comparative Methods in Stockholm

By Cristóbal Adam & Ria-Maria Adams

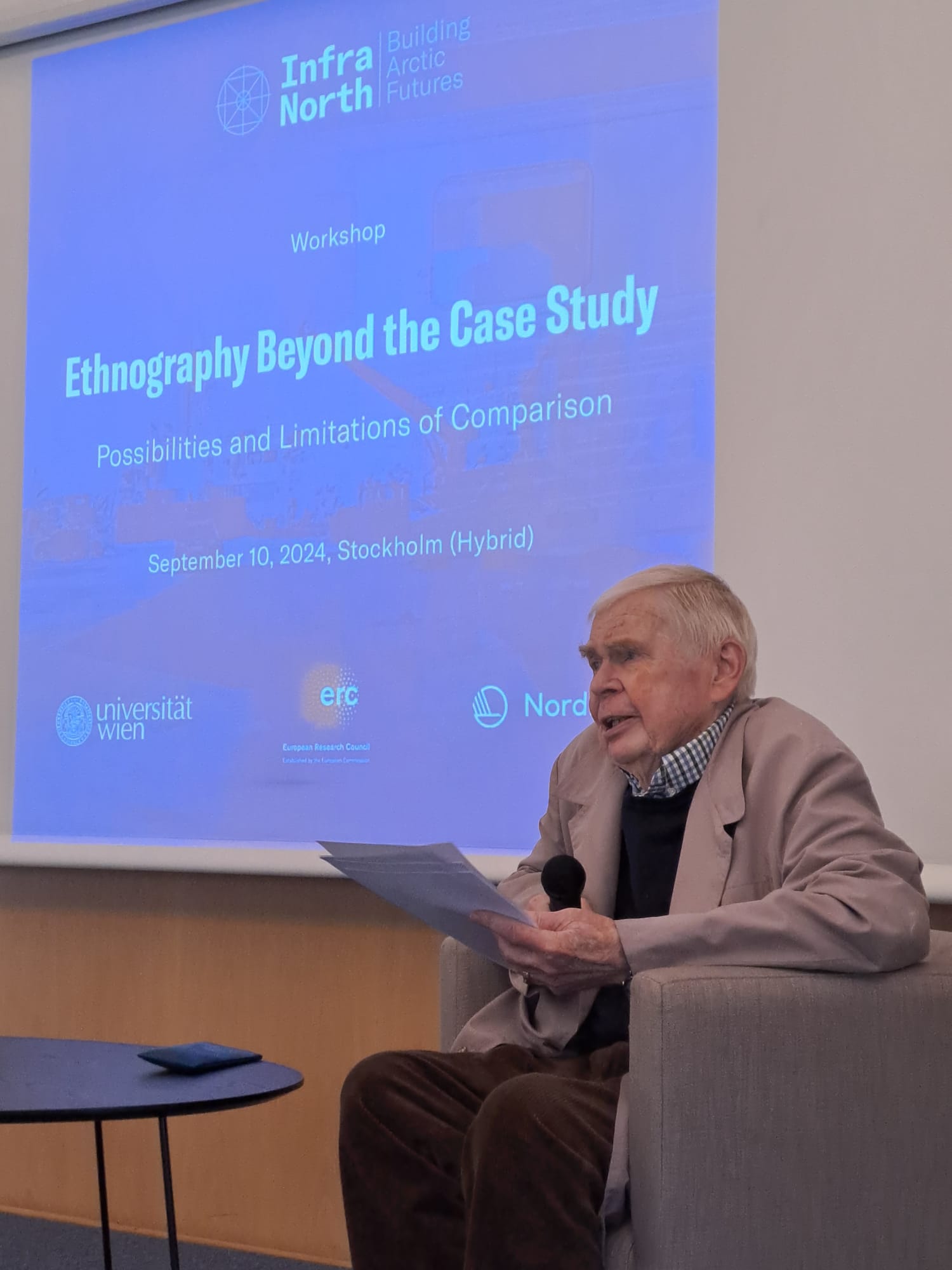

Comparison – a method so essential in anthropology, shapes our understandings of humans, societies, environments, and the diversity of cultures, yet it goes so often unnoticed because it’s so deeply ingrained in our research practices. Comparative methods have been a matter of debate in sociocultural anthropology, and the discipline has typically prioritized ethnographic fieldwork and engaged with questions about the uniqueness of a particular case study. On September 10-11, 2024, InfraNorth held a workshop in Stockholm, hosted by our team member Timothy Heleniak at Nordregio, which brought together researchers from various social science perspectives to discuss what can be gained by engaging in comparative endeavors. Rather than focusing solely on individual case studies and what each of them alone can teach us, we wanted to take a step back and ask ourselves, together with fellow researchers: what, how, and why do we use the method of comparison in our work?

In this two-day workshop, we were intrigued to find answers that go beyond particular case studies and to uncover common determinants that make comparison relevant, especially in large-scale comparative projects, like InfraNorth. In line with our project’s core theme, the focus of comparison centered on transport infrastructures.

Engagements with comparative anthropology

We were honored and delighted that Ulf Hannerz, a prominent anthropologist renowned for his work on globalization, urban culture, and transnationalism delivered a keynote address chronicling his lifelong engagement with comparative anthropology, including encounters with Peter Murdock and Andre Gingrich. Together with the latter, he co-edited the book Small Countries: Structures and Sensibilities (2017), an important contribution to the anthropological study of nation-states, which focused on the size and scale of a country as a determinant factor that shapes cultural identity, social structures and its role in transnational or global processes.

During the opening session, Hannerz also reminded us that while anthropologists should indeed consider studying future challenges like AI and climate change, they must also stay grounded in “what they are good at”—community studies. People continue to live in face-to-face settings, and community studies are essential for showing how people interact with each other and the environment around them.

Comparison in the study of socio-environmental entanglements

The second session featured researchers such as Leneisja Jungsberg (Nordregio), Corine Wood-Donnelly (Nord University), and Florian Stammler (Arctic Centre, University of Lapland). From different perspectives, the session highlighted the role of comparisons in analyzing the interaction between ecological and socio-cultural challenges. Also highlighted was the topic of relations, particularly the significance of infrastructural connections between individuals and collectives.

Leneisja Jungsberg presented her research on the adaptive governance of Arctic permafrost ecosystems and the identification of socio-ecological resilience enablers. Her study examines governance structures and processes of local and regional authorities in Arctic regions and investigates the role of nature-based solutions in mitigating permafrost thaw, highlighting both formal and informal ecosystem management techniques.

Corine Wood-Donnelly shared reflections from her experience as PI/coordinator of the EU-funded JUSTNORTH project, the results of which showed that many of the key challenges to the viability of sustainable development in the Arctic are rooted in systemic issues with origins far beyond the region. A rebalancing of the distributive, procedural, and recognitional aspects of justice is essential to nurture the foundations of sustainability in the Arctic region, she argued.

Florian Stammler, drawing on his ethnographic comparison of the Russian, Fennoscandian, and Greenlandic Arctic, argued that transportation infrastructures not only play a crucial role in determining the remoteness of places and settlements in Arctic countries but also influence notions of individuality and collectivity in Arctic societies. He encouraged us to pay particular attention to relations when conducting comparative work. Moreover, he highlighted that an affordance approach could be useful in understanding the relations between individuals and collectives.

Toward a comparative study of Arctic transport infrastructures

The third session consisted of presentations by the InfraNorth team, including a reflection on how the project is currently addressing the question of how to arrive at meaningful comparative perspectives, as well as some case study examples:

Peter Schweitzer shared insights into how the project seeks to compare without flattening the rich, but often idiosyncratic, ethnographies at hand. The project assumes that transportation infrastructure projects in the Arctic have certain distinctive qualities that differentiate them from similar projects elsewhere. Thus, its comparative ambition is pan-Arctic and not necessarily global. Within this framework, he argued that several comparative dimensions deserve to be explored: differences and similarities within the study regions, between different types of transport infrastructure, and within different political and temporal contexts. While the project does not assume that there is a constellation of transport infrastructures that applies equally across the Arctic, it aims to highlight the factors that give rise to similarities and differences within the region as a whole. In the end, this should also lead to preliminary “lessons learned” regarding the positive and negative impacts of transportation infrastructure projects on the well-being of communities in Arctic contexts.

In her presentation, Olga Povoroznyuk drew upon three case studies of seaport expansion projects in Nome (USA), Kirkenes (Norway), and Tiksi (Russia), to examine the social, economic, and cultural implications of infrastructural development in the newly divided Arctic. She focuses on imagined, emergent, and reconfigured Arctic (dis-)connections to explore local attitudes, narratives, and affordances of seaport infrastructure. With her ethnographic field data from different periods, archival materials, media reports, and policy documents, she explored the possibilities and limitations of comparison of similar infrastructure projects in different national contexts.

Alexandra Meyer and Ria-Maria Adams presented a comparative study they are conducting together with Sophie Elixhauser on the role airports play or are expected to play in daily life and community development in three remote Arctic communities (Longyearbyen, Rovaniemi, and Tasiilaq), as well as the local effects, promises, and fears associated with the increased accessibility that existing and planned airports provide to the communities. They emphasized an inductive comparative approach that focuses on the role of airports and their anticipated impact on the daily lives of local residents and community development.

Comparison in the anthropology of infrastructure

The final session included different approaches to the anthropology of infrastructure by Johan Lindquist and Chakad Ojani, both from Stockholm University. Their presentations raised questions about how infrastructures shape transnational social dynamics, as well as how small-scale infrastructures can impact larger processes or social settings and vice versa.

Johan Lindquist discussed an ongoing project centered on ‘migrant preparatory training’ for low-skilled documented international labor migrants from sending to receiving countries. The project focuses on how this type of training and related migration policies have spread across the Global South from Asia to Africa. Based on ethnographic research in Ethiopia and Indonesia, the project considers training centers, particularly for female domestic workers, as sites that lend themselves to a concern with comparison as well as an infrastructure of transnational circulation.

Finally, in his presentation, Chakad Ojani juxtaposed two ethnographic projects on small and large infrastructures. While the first deals with fog catchers in Lima, Peru, the second examines large-scale infrastructures in Sweden (including a rocket launch site, ground stations, and satellite constellations in orbit). Whereas the first project examines how small, improvised infrastructures instigate or redirect larger processes, the second is primarily concerned with how small social settings sometimes adapt or modulate large infrastructures. Using scale as a basis for comparison, Ojani reflected on what this difference in focus can tell us about the anthropology of infrastructures more broadly.

Philipp Budka, Elena Davydova, and Katrin Schmid moderated the sessions and discussions throughout the first day and provided input from their field sites on the following day. With all the insights and new thoughts from day one, we started the second day of our workshop in Stockholm not only with a great fika with cardamom buns, but also by tackling the specific questions together as a team and with our speakers: What, how and why to compare. While topics and keywords (such as temporality, regional specifics, values, scenario-building exercises, cognitive and vertical dimensions, and material and immaterial comparisons) were discussed at length, we concluded that comparison is not a method to be shelved, but is very much alive and practiced in our research. This enables our work to find the particularities and specificities we are looking for when trying to understand transport infrastructures in the Arctic through different lenses.