Bridging Past and Present: Archival Research in Ethnographic Studies of Transport Infrastructures

By Philipp Budka

When preparing for fieldwork on transport infrastructures in Manitoba, Canada, I planned to supplement my ethnographic research with archival data. I initially expected to conduct most of this research online from my office in Vienna but soon realized access was limited – while some archival records were digitized and available online, many were not. To better understand the history and transformation of key infrastructures like the Hudson Bay Railway and the Port of Churchill, I needed to visit Canadian archives in person. This post reflects on my experiences with archival research as part of an ethnographic study on transport infrastructures.

Archives in Social Science Research

In addition to serving as research tools, archives have long been central to debates in the social sciences on power, hegemony, and knowledge production, as exemplified by Michel Foucault’s exploration of how archives shape and structure knowledge. Conceptually, archives exist at the intersection of memory and forgetting, serving as mediators between record creators, the public, and the past and present. Archives are not neutral repositories; they are shaped by politics and purpose. In ethnographic research, this calls for a reflective approach that acknowledges their contextual dimensions. As David Zeitlyn argues, archives are “complex social organizations” rather than static collections.

Archives also shape infrastructures, though this relationship is often overlooked. Alessandro Rippa emphasizes how infrastructures, such as road projects, both influence and are influenced by archival practices. Initially, I understood archives as institutional spaces for accessing records, but my ethnographic research challenged this view. Perhaps people—research partners and interlocutors—can also be seen as living archives, sharing their experiences, knowledge, and even archival materials with researchers.

From the Personal to the Institutional

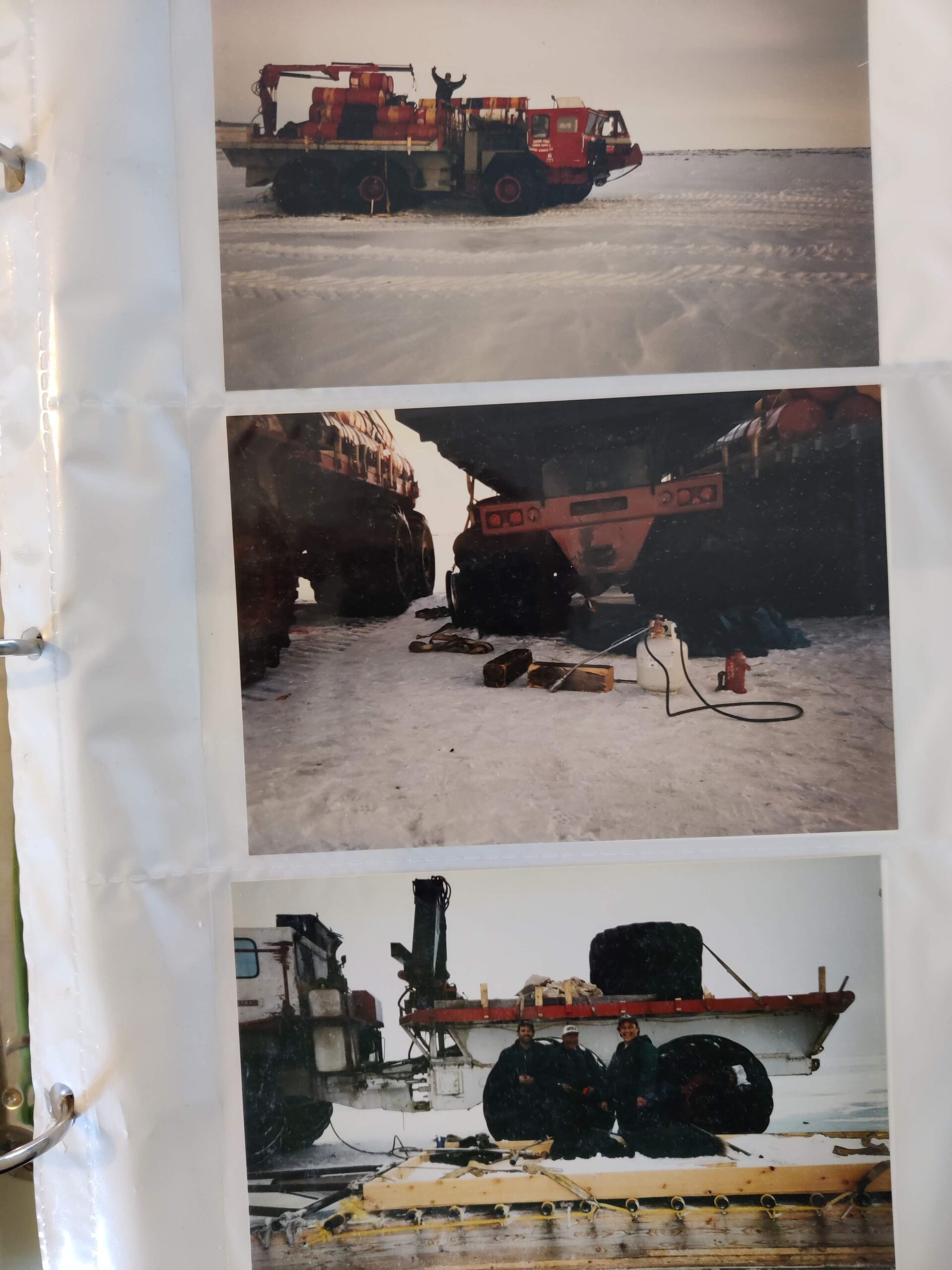

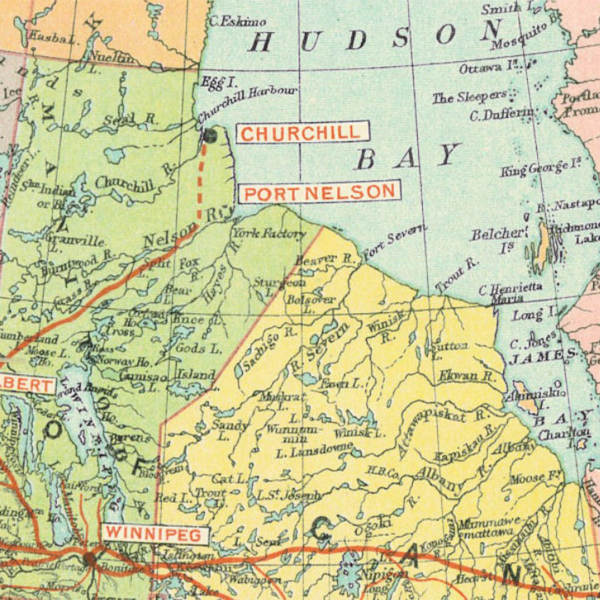

During my third field trip to Churchill in the summer of 2023, one of my interlocutors shared a collection of documents he had compiled over the years. He had systematically photocopied and digitized newspaper articles and reports that he considered relevant to the history of the Port of Churchill. Among these was the “Palmer Report” from 1927, which played a key role in the decision to establish Churchill, rather than Port Nelson, as the terminus of the Hudson Bay Railway for shipping grain from Canada’s prairie provinces. This debate over the most viable route resurfaced in 2023 with a new proposal to designate Port Nelson as the endpoint for a newly proposed utility corridor aimed at exporting Canadian natural resources.

Eighteen months earlier, at the end of my first field trip to Churchill in February 2022, I arranged an interview with an elderly person who was described to me as “the town’s historian and archivist.” After our conversation, she introduced me to what she called the “community archives,” housed in a small room within the public library. There, she and her colleagues from the Churchill Ladies Club preserved a diverse collection of documents – including photographs, letters, and newspaper clippings – donated by various institutions and individuals in Churchill. “This is not really organized,” she admitted. Nevertheless, the Ladies Club used these archives to publish a comprehensive history of Churchill, which became a key source for my ethnographic research.

In October 2022, I returned to Manitoba, prepared to visit the provincial archives in Winnipeg – or so I thought. I soon realized that finding specific materials on the Hudson Bay Railway, the port, and Churchill required precise research questions. However, with the help of the Archives of Manitoba staff, I uncovered valuable records, reports, and texts that enriched the historical contextualization of my ethnographic research.

A year later, I returned to Canada, this time visiting the country’s largest archive – Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa – to continue the archival research I had begun in Winnipeg. While I was able to retrieve relevant records and materials, I encountered a new challenge: key documents, such as those on the privatization of the Hudson Bay Railway in the 1990s, were restricted and would remain inaccessible for another 20 years.

To request access to restricted records, one must submit an Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) form. The request must be filed from within Canada, either by a citizen or a visitor; it cannot be submitted from outside the country. As a result, some researchers choose to hire a local assistant to continue their archival work.

I was once again reminded that it is rarely possible to simply “take a quick look” at archived material. Retrieving documents can take several days, and having well-defined research questions is essential to streamline the process. A staff member at the archive’s information desk informed me that accessing restricted documents can take weeks, months, or even years.

News Media and Internet Archives

Accessing online archives of regional and provincial newspapers, such as the Thompson Citizen and the Winnipeg Free Press, was much easier. However, when websites like the Citizen ceased publication, the Internet Archive became invaluable for recovering seemingly lost information. Unfortunately, the newspaper’s original repository and search function are no longer accessible in the archived version.

Final Thoughts

Archival research complements traditional ethnographic methods, such as interviews and participant observation, by providing access to historical data and enabling longitudinal and diachronic analysis. Integrating archival materials with ethnographic fieldwork enables a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena, such as the sociocultural impact of transport infrastructure changes in Northern Manitoba, Canada.

Ethnographic research participants, partners, and interlocutors can be understood as living archives, sharing their experiences, knowledge, and sometimes even physical documents. Through their memories and narratives, they provide valuable insights into both the present and the past.